Rock art was often deliberately made were communication with the spirits was believed to be good. It was therefore made in caves and shelters, on steep cliffs, high in the mountains and on the shore — a range of localities all concidered transitional spaces between cosmic worlds. This emphasises that rock art is often jast one part of a broader ritual landscape.

An examination of meanings associated with bears among early hunter-gatherer-fisher populations in northern Fennoscandia, based on beliefs and ritual practices in the

ethnohistoric record, indicates that they were an animal attributed multiple meanings in prehistoric as well as historic times. They were clan ancestors, spirit masters and symbols of power and reincarnation such as rebirth and the change of seasons. The evidence indicates a pattern of local variation and identities rather than a uniform regional pattern, and some large-scale differences from the coastal area of Norway in the west to Karelia in the east.

Rock art is defined as systematic and man-made depressions or paintings on a smooth rock surface. In contrast to other cultural monuments, they have hardly any ecological importance. Nevertheless rock art sites should be regarded as a part of the landscape, both with respect to interpretation and preservation. The method of gluing together fragmented rock art panels with an organic glue, and the repairing of cracks on rock art panels by mortar, are criticised. The author raises doubts about the ‘crumbling effect’ of mosses and the effect of ‘aggressive lichen’, postulated by other authors. The need for a long time perspective and international co-operation in rock art reservation and conservation is underlined, and it is emphasized that experiments with new methods of conservation should be done on panels without rock art. Based on observations of an accidentally covered rock art panel in Gudbrandsdalen, Norway, a new and reversible method for stabilisation of severely weathered rock art panels is proposed, using dissolved calcium carbonate which is precipitated in a calcification process on the weathered rock and in cracks.

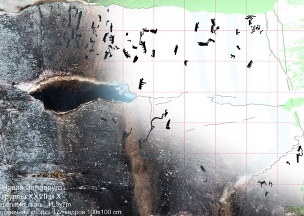

The paper summarises the history of discovery, study and results of recent field documentation and protection work on Karelian rock art — unique cultural and historical treasure of Northern Europe, coming to us from Neolithic epoch. The international Karelian-Norwegian project “Preservation of Karelian petroglyphs (1998–2001)“ has contributed much in this activity. The project was funded by the Cultural Heritage Directorate of the Ministry for Environment of Norway and Karelian Ministry of Culture. Petroglyphs electronic database is the goal achievement of the project.It contains large and various information on Karelian carvings which could promote further research, protection and managing of the sites.

The study proves the need for making and later using of ancient rock image mosaic flat panoramic photos in order to monitor rock surfaces condition and to promote the monument. The study contains the description of the technics the photographer dealing with that flat panoramic photos uses and some results of his work carried out on horizontal rock surfaces of the Onega and Belomorsk petroglyph sites (Republic of Karelia).

The study of Onega and Belomorsk petroglyphs can be divided into four stages. Each of them has its own milestones, significant events, facts and names.

The first stage covers the period from 1848 to 1926.